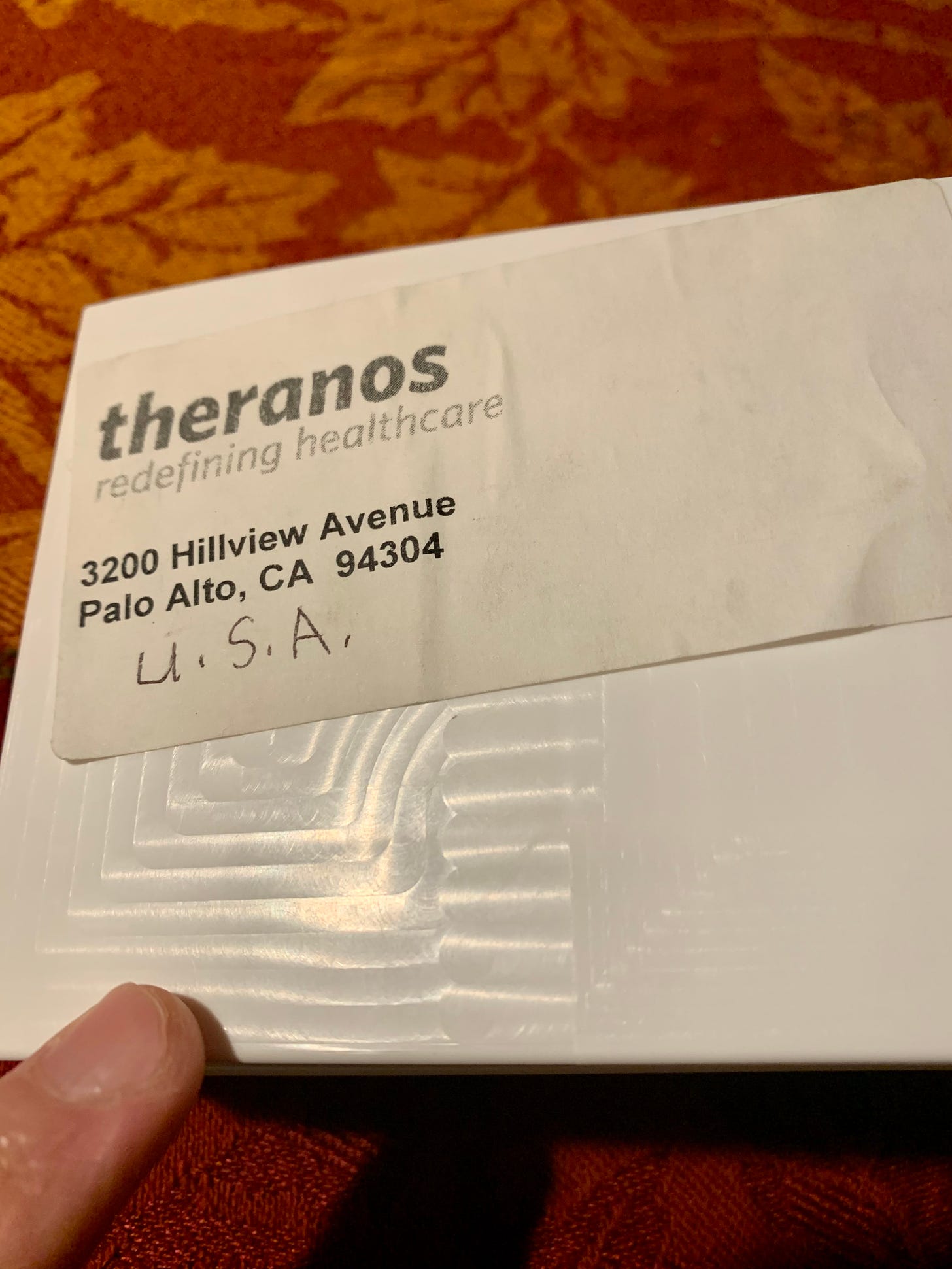

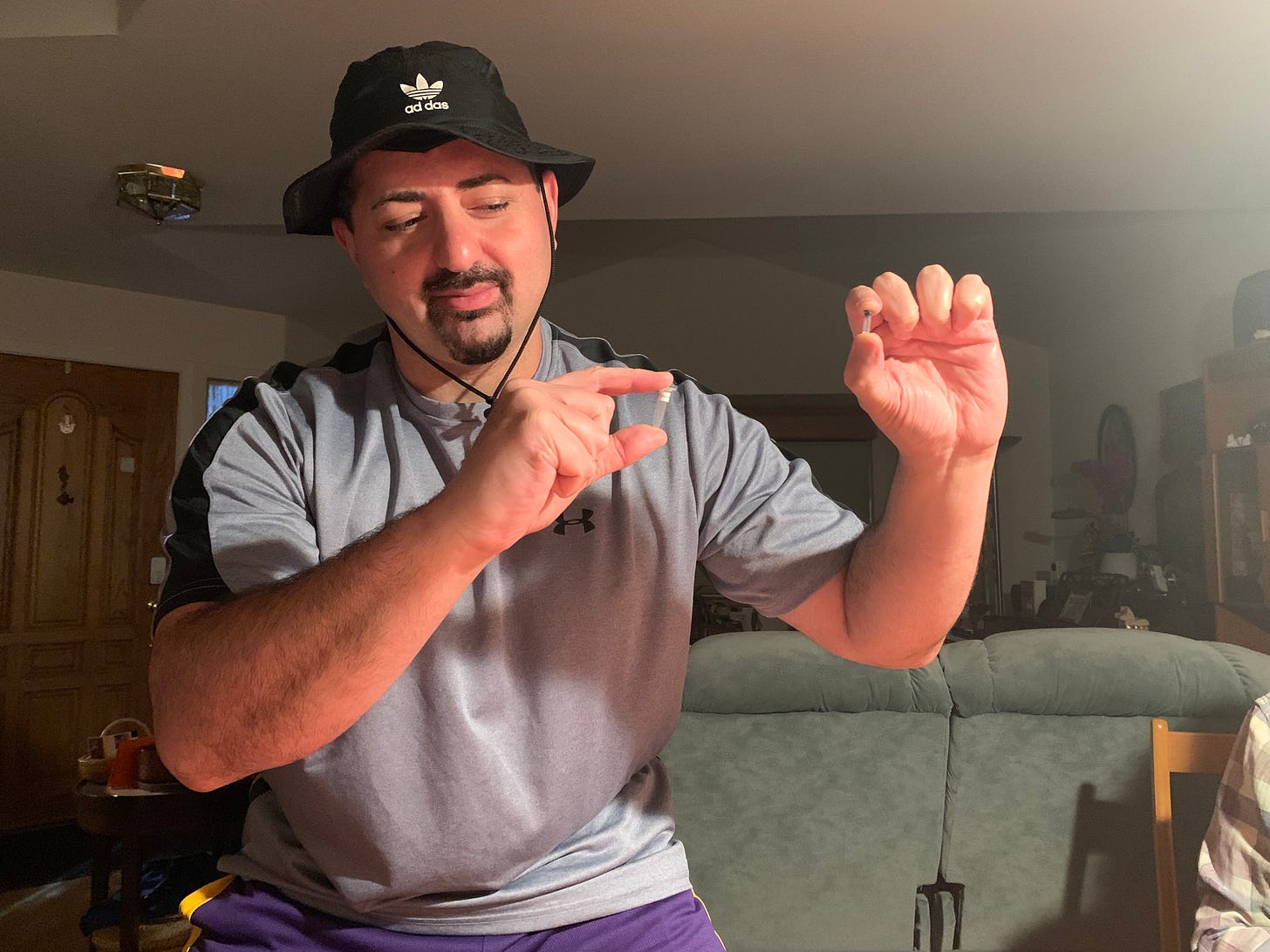

When my neighbor showed me a Theranos cartridge and two vials, I immediately recognized the “razorblade” model: the Edison was supposed to be the affordable razor, and the cartridges the expensive replacement blades.

In theory, if Theranos' hardware had problems, as long as its components provided revenue, the company could keep tinkering until it achieved perfection.

Of course theory doesn't always become reality, and Theranos' cartridges reveal unbridled ambition. First, in order for cartridges to be priced fairly and sustainably, each patient—along with many others in the same 30 minutes' timeframe—probably needed to order multiple tests. If most patients sought only one blood test, it's possible the cartridge's cost, when including labor, would preclude profit. (Due to contamination and storage issues, I rejected re-using cartridges.) Second, the cartridge's design allowed approximately one millimeter between each slot, meaning a robotic arm moving vials in and out needed to function perfectly.

The startup world attracts reasonable and unreasonable optimists. Theranos' business model appears to have assumed perfection from inception--and that's before conquering software bugs, federal regulations, and insurance reimbursements.

Other than my external courtroom investigation, Day 16 brought more of the same. Former Safeway CEO Steven Burd, an ideal witness, could have single-handedly turned the case; however, his testimony was neutral, which, under burden of proof rules, favors Elizabeth Holmes. Though Burd confirmed he was told "one cartridge will satisfy 95% of all the CPT codes"--with the remaining 5% of "esoteric tests [being] done with cartridges manufactured to the need"--emails establish he knew or accepted the Edison as a work in progress, including with respect to fingerstick testing:

"The sooner we get to 'finger stick' the better we will be." (September 12, 2012, Burd to Holmes)

"it looks like your lab work is all being sent to Utah, not UCSF and not being done on-site... I realize this is a temporary process..." (September 25, 2021, Burd to Holmes)

At the same time, Burd believed delays were caused by non-hardware-related obstacles: “I didn't think it was the box.” On cross-examination, Burd acknowledged regulatory risks and admitted Safeway “spent hundreds of hours on… due diligence,” but neither disclosure was unexpected. Most favorable to the defense was a "Termination Without Cause" provision in the 2010 contract: “Safeway will determine in its sole discretion whether the pilot of the Program” has met Safeway's satisfaction, and in the event of dissatisfaction, Safeway could terminate the Theranos relationship after January 15, 2011. Since no evidence indicated this provision was utilized, on Day 16, I still do not see a crime. I see two unreasonable optimists who should have been reined in by their respective boards.

The government may have better luck with former Walgreens CFO Wade Miquelon, who understood Theranos' potential better than most: "we will be the gateway into primary care and the gateway out." When asked about fingerstick tests, Miquelon testified he thought it worked for some but not all. (We now know none of Theranos' fingerstick tests on patients worked reliably.) Regarding impediments to "going live," Miquelon, like Burd, cited non-hardware issues like "perfecting reagents." Miquelon's direct experience with retail pharmacy operations makes him highly qualified to testify against Elizabeth Holmes. If you favor the government, tomorrow is the day reasonable doubt disappears or takes a semi-permanent seat in the courtroom.

© Matthew Mehdi Rafat (2021)

Update: the above photos do not show the dilution or centrifugal part of the analyzer process. Regarding potential reasons for variance or quality failure, an email indicated one "sample became contaminated during centrifugation."